Table of contents

Rubrics can help

For summative assignments it is recommended to add a rubric to your assignment. It will make grading more consistent between different graders, speed up grading, and give students insight into how their grades came into being.

A rubric is an answer model for assignments, usually in the form of a matrix or grid. It is a tool used to interpret and grade students’ work against criteria and standards derived from the learning objectives of the assignment.

| Rubrics can help lecturers | Rubrics can help students |

|---|---|

|

|

Adopted from https://teachonline.asu.edu/2019/02/best-practices-for-designing-effective-rubrics/

1. How to create a rubric

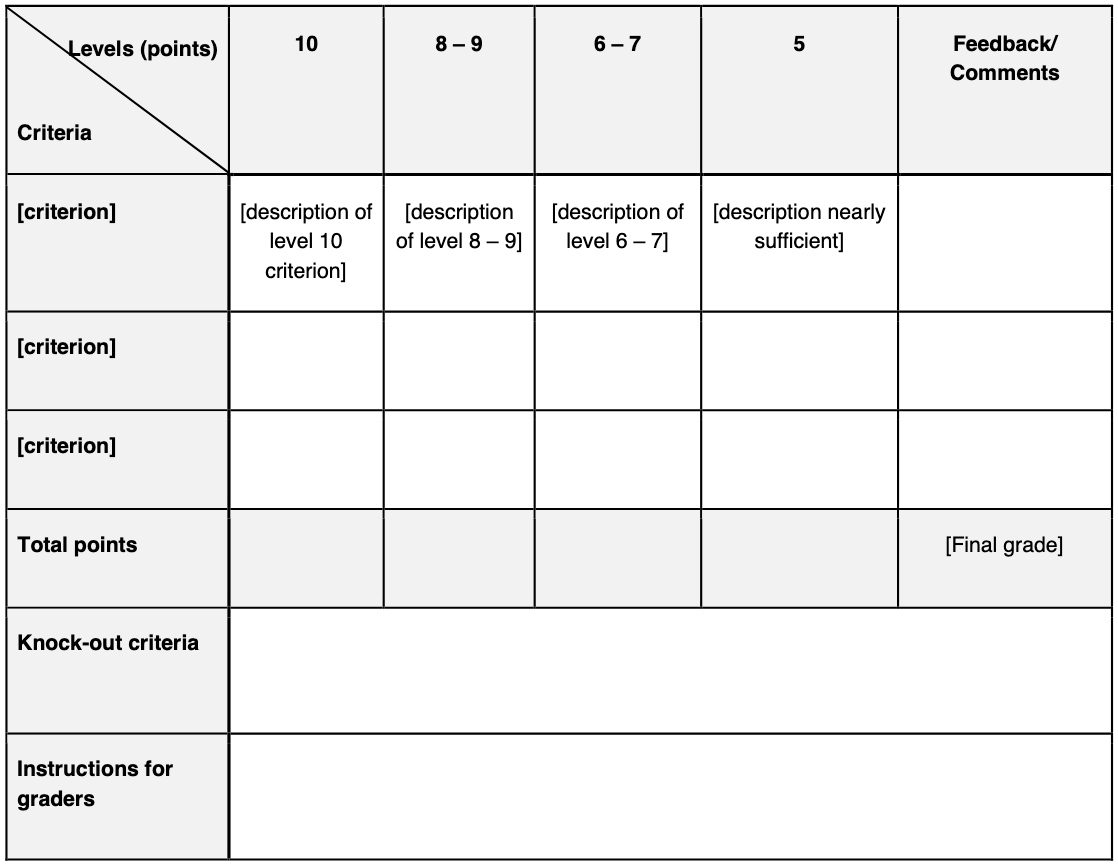

We know that creating a rubric takes time. The step-by-step plan below will help you set up a rubric as effectively as possible. This template is used at TU Delft to develop rubrics.

If the assignment has been well articulated, with clear and specific learning goals in mind, the language for your rubric can come straight from the assignment as written. Otherwise, try to unpack the assignment, identifying areas that are not articulated clearly. If the learning objectives are too vague, your rubric will be less useful (and your students will have a difficult time understanding your expectations). If, on the other hand, your stated objectives are too mechanistic or specific, your rubric will not accurately reflect your grading expectations. Assess how your course relates to the learning outcome. Are the learning objectives concrete enough?

Another approach is to figure out what areas really matter to the quality of the work that’s being produced. Whether it’s an essay, a project, a digital story, a portfolio or a presentation, what evidence of the student’s learning will you assess in the final product?

- List all the possible criteria you might want students to demonstrate in the assignment. Include criteria for the process of creating the product and the quality of the product.

- Decide which of those criteria are “non-negotiable.”

- Ideally, your rubric will have three to five performance criteria.

- If you’re having a hard time deciding, prioritize the criteria by asking:

- What are the learning outcomes of this assignment?

- Which learning outcomes will be listed in the rubric?

- Which skills are essential at competent or proficiency levels for the assignment to be complete?

Determine how you are able to see when and at what level the student has achieved a learning objective. Aggregate the criteria to come to a clear-cut number. Formulate the criteria in key words.

For each criterion, determine what a ‘pass’ performance should consist of. Describe these performances in 1 or 2 sentences arranged into a column of descriptors. Specify these descriptors to the same level as the standard (therefore, avoid relative descriptions such as ‘better than…’, etc). Determine ‘unsatisfactory’ and ‘good’ (and other scoring). Carefully check that the descriptors are sufficiently distinguishable.

These often are the basic requirements for submission, like name and student id, timely submission, word count, number of pages, quality of images as set in the assignment.

Describe when a performance is considered so poor that it falls below even extremely unsatisfactory, or alternatively so well done that the performance can be considered outstanding.

Determine whether all criteria will be considered in equal measure. Clarify how you will determine the end score and end appraisal.

Try to fit the rubric onto one sheet of A4. Summarise descriptors, aggregate and leave room for interpretation.

It is essential to try your rubric out and make sure it accurately reflects your grading expectations. If available, use sample work from previous semesters. Alternatively, it is recommended to test your rubric on a sampling of student papers and then revise the rubric before you grade the rest. But be aware that you are not substantially altering the grading criteria.

A rubric is never really complete. Each period, you may want to evaluate where any ambiguities appeared and adjust these accordingly. Use your rubric to clarify your assignments and to improve your teaching.

2.Tips for keeping rubrics clear, fair and efficient

- You might want to order the columns from ‘best’ to ‘worst’ level, so that students can directly read the expectations for the highest level next to the criteria and therefore can quickly determine what is expected from them.

- In case your columns are ordered from ‘worst’, to ‘best, the good thing is that you can diminish the text in the descriptors, by making, for example, the ‘good’ and ‘excellent’ level build upon the ‘sufficient’ level.

- An example of these ‘incremental’ descriptors, using ‘…’ for the part that is repeated is the following:

- Sufficient: ‘Mathematical formulation is correct and variables are individually explained’

- Good: ‘…in relation to each other’

- Excellent: ‘…and to the model.’

- This helps to keep the rubric simple and clear in a glance.

- Consider using the rubric for peer feedback for, for example, a draft product. You may replace the grade calculation table by a simple formula, if that suits you better, whether or not you add some minimum levels for all or for certain criteria or criteria groups.

- You might (or might not) find it useful to give a better overview by clustering criteria into criteria groups. For example: split the criteria group ‘writing style’ into the criteria ‘clarity’, ‘conciseness’, and ‘objectivity’.

- About knock-out criteria: Instead of giving a maximum number of pages excluding figures, you might want to give a maximum number of words, including captions (which makes it easier to check). This might prevent students from using terribly small fonts or placing all figures at the end of their report (making it more difficult to read & grade) to enable them to count the number of pages without figures.

- When you are grading with a number of colleagues, you will most likely have a meeting (sometimes called ‘calibration session’) in which you will all grade one or a couple of products (reports, code, etc.) and discuss how you make the grading as objective and uniform as possible and what to do in case you are questioning how to grade a particular criterion or student’s product.

- Ensure that assessment rubrics are prepared and available for students well before they begin work on tasks, so that the rubric contributes to their learning as they complete the work. You also may want to consider practicing using rubrics in class. Have students assess their own, their peers’ and others’ work.

- Provide the assessment rubric for a task to students early, to increase its value as a learning tool. For example, you might distribute it as part of the assignment briefing. This helps students understand the assignment and allows them to raise any concerns or questions about the assignment and how it will be assessed.

- Write rubrics in plain English and phrase them so that they are as unambiguous as possible.

- Involve students in improving the rubric and invite them to give feedback and suggestions to rephrase.

- You could also use the rubrics tool in Brightspace. This way your rubrics are directly accessible when grading assignments in the Brightspace Assignment tool.

Checklist for rubrics

- Is it clear what the weightings of the criteria are?

- Is it clear how the grade is derived?

- Does performance at the minimum level of a pass lead to a pass grade?

- Is it possible to get a 10, judging by the criteria descriptors?

- Is it feasible to get a 10, judging by the descriptors of the highest levels?

- Are the descriptors objectively formulated (not just ‘sufficient’ ‘excellent’)?

- Are the descriptors specific and clear?

- Are the descriptors of each criterion unique (no overlap between descriptors of adjacent levels)?

- Does the rubric give a good overview at first glance (not too many rows or columns)? The rubric fits on one A4. The lay-out is clear.

- Is the amount of details suitable (not too detailed / no information that belongs in a course book)?

- Does it allow for specific (individual) feedback?

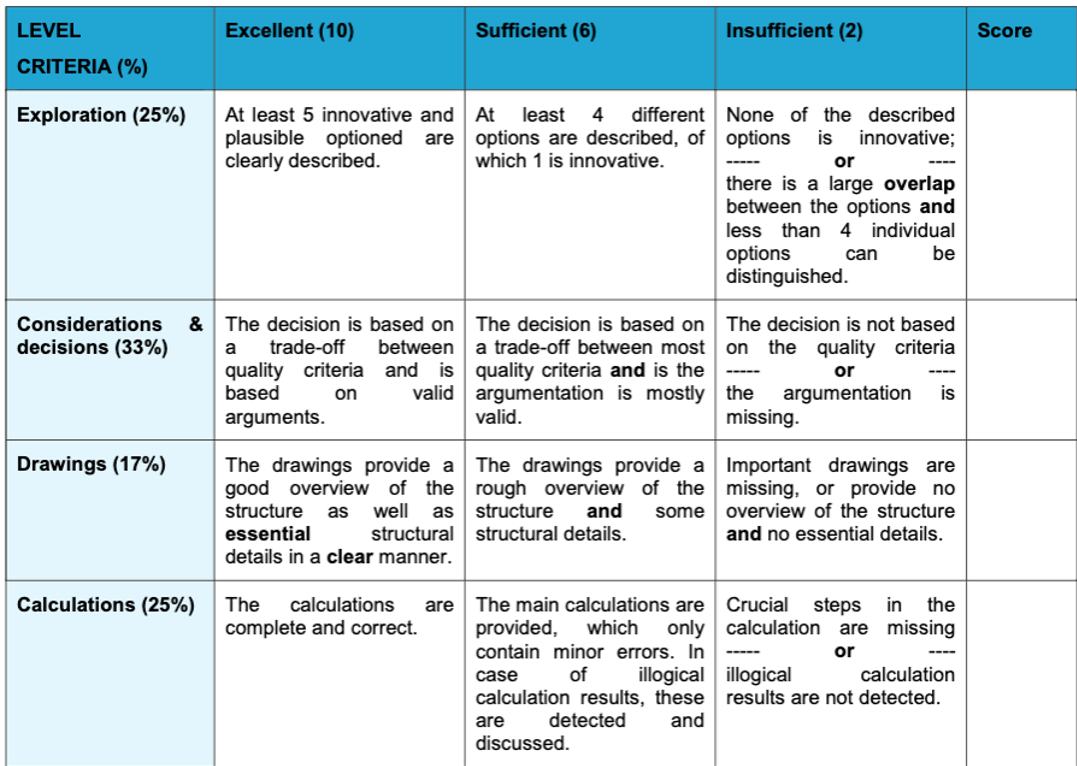

Example Rubric

If you use a Brightspace rubric, it could look like the one below. You can divide the rubric into subquestions and their steps and mandatory items (e.g. units and rounding) and/or criteria (e.g. explanation results and correctness of conclusion). When scoring the students’ work, click on the applicable cell for each row and the total score is automatically calculated.

![]() This work by TU Delft is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.

This work by TU Delft is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.